Why artists should care about HDR

Have you ever been awestruck at a scene of shafts of sunlight cast through clouds, mesmerized by the flames roiling in a campfire, or captivated by the saturated rim lighting in someone’s hair?

I have.

Have you ever tried to capture the moment with a photograph, only to find it dull and lifeless after the fact? At the very least, it didn’t capture the feeling of that moment very well?

You’re not alone.

I’m here to tell you that if you’ve ever had a moment like this with a camera, your editing software has conspired to wash out the photo and leave you hopelessly disappointed.

Okay, okay, that’s a slight exaggeration. There is a reason why, but we are finally at a point in history where you are in a position to do something about it: HDR is here, baby!

Sort of.

First of all, what is wrong with SDR?

Your eyes can see significantly more highlights than a computer monitor. Because we process visual data relatively, you probably don’t even recognize how significant the difference is.

Some rough baseline numbers:

- Printers & inks capture around 4 stops of light

- Computer monitors can show 6-8 stops of light

- DSLR/Mirrorless cameras can record 12-15 stops of light

- Human vision can see 10-16+ stops of light at the same time

- Human vision can see up to as much as 30 stops if you include allowing your vision to slowly adjust from very dark to very bright conditions

What did I mean with that comment about processing visual data relatively? When you look at a computer monitor, your brain automatically compares colors on the screen to what it thinks “white” is on the screen. That’s why photos still look natural even when you turn the brightness up/down, or when you use your computer in a light/dark room. It’s also why you can adjust the color temperature of the screen at night and it feels natural after a while.

LEDs are really bright these days, why don’t we just crank up the brightness?

There are two reasons. The first is that LCD tech has limited contrast. You can increase the brightness of the brights, but it will also make blacks into greys. Fancier panels are using tech like quantom dots (QLED) and/or local-dimming to improve the contrast though, which leads us to the second problem: discomfort. If everything becomes bright then normal websites would be physically painful to look at. Normal daytime photo/video would be overblown, TV menus would a disaster, and it would be an all-around bad time. Even if everyone in the world decided that some shade of grey was the new “white”, everyone with a “standard” screen would see everything become incredibly dim just in case HDR content was going to be displayed, and they would especially suffer from the contrast issue above.

Okay, so what is the solution?

First, let’s think about “white” as something a bit more useful. Think about a sheet of white paper sitting in a room. The sheet is diffuse, so you don’t have to worry about any sharp reflections from what is near it, and it’s brightness depends on the brightness of the room. Our fleshy meat computers would quickly recognize a sheet of paper as “white” very quickly in all sorts of lighting conditions.

Importantly, although we recognize this “diffuse paper white” as inherently white, it’s not by any means the brightest thing in the room. Lights, windows, and specular reflections are often much brighter than paper white, but paper white is still a good baseline for how bright a surface should be if you wanted to, say, put writing on it. If we decouple paper white from “maximum possible brightness”, we can have our cake and eat it too! We can have SDR content (contained within the paper) and HDR content (including light sources) in the same scene! For that matter, we can even let HDR content play on SDR screens by just compressing the highlights like we’ve done forever!

Sort of.

What is highlight compression?

If there’s more dynamic range than you are capable of capturing or displaying, you’ve got to make a decision on what to do. One option is to just clip each of the RGB values to the limits of what the display can handle. If you have a super-red color of rgb(278, 0, 0) you would just clip it to rgb(255, 0, 0). While this makes sense for a solitary primary color, it falls apart pretty quickly because it creates hard lines in photos where the clipping occurs, throws away all that wonderful highlight data entirely, and if only one or two channels are clipped it can actually change the color dramatically.

A more aesthetically pleasing solution is to apply highlight compression, where you sort of taper off the highlights towards your reference (paper) white. This preserves some of the highlight detail, so you can see the shape of things even if it’s washed out, and instead of having funky broken colors where clipping happens you just get closer and closer to white instead which is more aesthetically pleasing.

To be clear, highlight compression only makes sense if you start with more color data than you end up with, but that leads me to my next point:

How do I capture more color data than a typical screen can display?

If you’ve got a DSLR or mirrorless camera chances are you’ve been taking HDR pictures for years without knowing it. The whole reason we’re able to do highlight compression in the first place is that our cameras have been capturing 12+ stops of brightness, but photo editors have to compress it down to more like 6-8 stops for computer screens. If you have taken RAW photos where the histogram is smushed over towards the right, but there’s no actual clipping happening, that’s highlight compression at work! RAW is often pitched as a way to get “highlight recovery” since you can drag the exposure slider to darken the photo after the fact and have it still look good, but with the right screen you could see all the details in the darks and all the details in the brights at the same time!

Alright enough theory, what does HDR look like?

For the last several years, Apple has been pushing really decent HDR screens on their top-line Macbooks, iPads, and iPhones, most flagship Android phones support some level of HDR, and a good chunk of TVs have HDR support too. Don’t get me wrong, we’re still in the early-adoption phase here, but this is not just for content creators that can afford $20,000 studio HDR monitors anymore. Just to be safe though, I’m going to demonstrate what HDR looks like assuming you are reading this with an SDR screen.

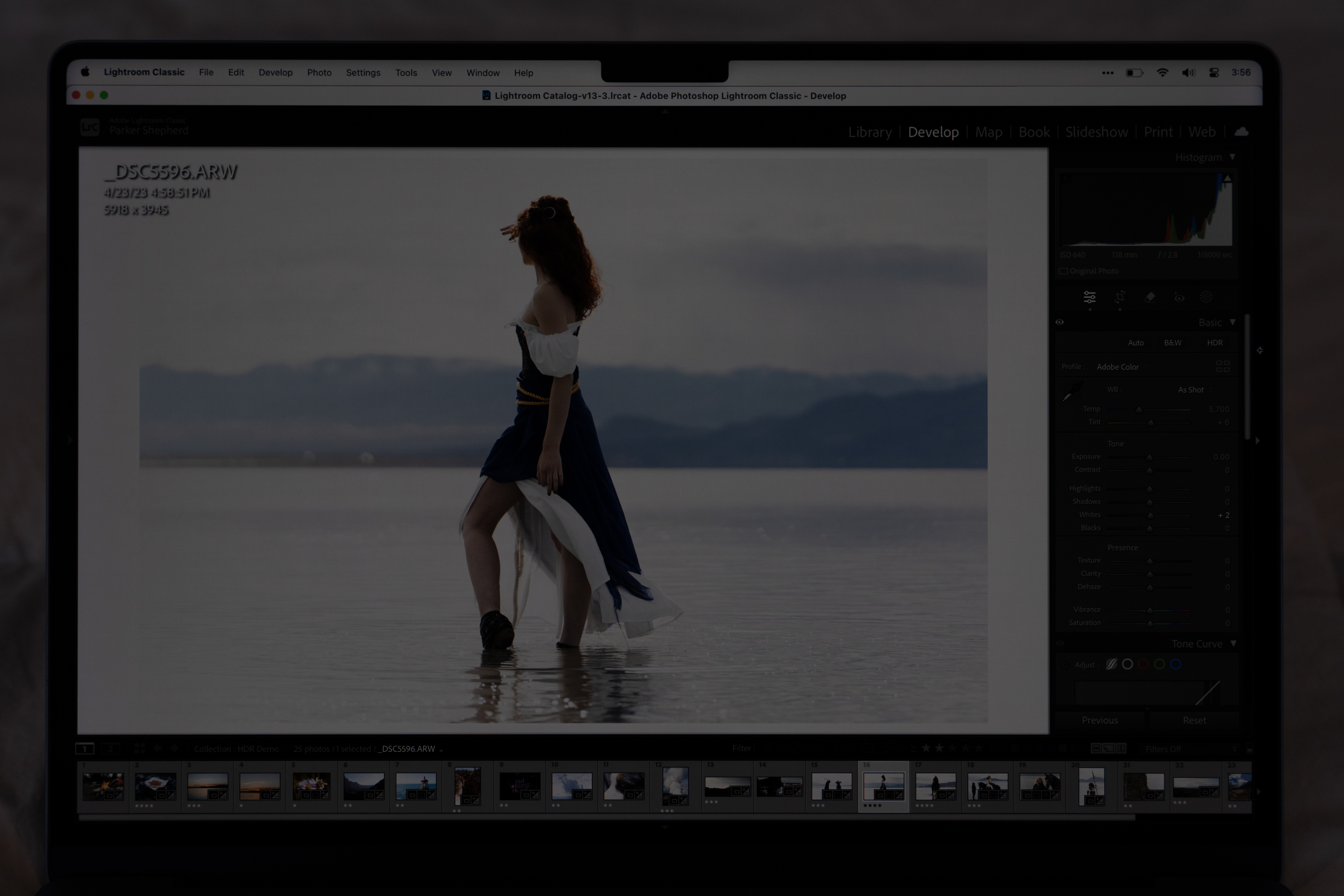

How am I going to do that? Remember that vision is relative, so I just need to convince you that some shade of grey is actually paper white. I can’t make your whole computer cooperate, so you’re going to have to play along for a bit. This is going to make sense if you look at the images in full screen, in a dark room. Basically, I’m going to show you an underexposed photo, but I need you to take my word that it’s actually correctly exposed for what I’m trying to show you. The Macbook in the photos was reasonably bright, in a reasonably bright room.

To be clear, this is a pretty extreme example on a screen that can display 4 stops of dynamic range (but only when the brightness is set to 50%). Adding that much brightness beyond paper white is bordering on rude to the viewer, but here’s my justification:

- I’m showing off in a blog post

- I’ve prioritized exposing the photo so that you can see the detail the model, not the background

- This was really how the scene looked when I took the photo. Shooting into the sunset had me squinting when I was there, so I feel honor bound to make you squint when you look at the photo

Okay, so #2 could be addresssed with masking to darken the background and brighten the foreground, but as silly as #3 sounds a big part of why I like photography in the first place is I love being transported to a moment in time, not just seeing something aesthetic. When you compress the true dynamic range of a scene, you are erasing a little bit of reality and your brain does know it even if you’ve learned to make it subtle.

Wait a minute, I thought this whole post was about why artists should care about HDR?

Yes, it’s true, I went on this whole rant about dynamic range trying to “preserve reality” and phsyical media has even less dynamic range than SDR let alone HDR monitors. Am I arguing artists everywhere should switch to digital media to chase realism in a subjective field?

Absolutely not.

BUT

HDR, as a tool for preserving reality, is an incredible way to improve your reference pipeline. Highlight compression is only one way to deal with a low dynamic range output, and that’s what you get if you take a photo and then let your editor convert it for use on an SDR screen. If you are working on a scene with saturated highlights, highlight compression will make your scene more dull and washed out than what you started with, and it should be up to you if you want to preserve contrast or preserve color.

At the very least, working with an HDR pipeline is incredibly instructive on how dynamic range affects some scenes more than others. I learned that closing one eye can help you see what scenes are only interesting because of depth that is lost in a photograph, and HDR has taught me more about what scenes are only interesting because of dynamic range.

How do I actually start using HDR for reference photography?

To start with, you need a screen that can display HDR content. Apple’s “XDR” displays in Macbooks, iPads, and iPhones are some of the best options here, especially for the price (standalone studio HDR monitors can cost more than a XDR Macbook 😬). Apple’s software support is also the best out there when using an XDR screen. SDR and HDR content works seamlessly, and the HDR content scales with your chosen brightness setting in a very natural way.

The next best option is getting an HDR display and using it with your current setup (Mac or Windows). I’d shoot for 1200 or more nits to make sure it’s an actual HDR monitor and not just an SDR monitor with marketing garbage. Greg Benz often links to some good monitors from his blog. With an external monitor, you’re kind of locked in on brightness, so you can’t get a full 4 stops like I showed in my demo photo, you’ll be locked to the brightness built into the monitor (1500 nits is around 2 extra stops). Hopefully Apple & Microsoft will fix this but I wouldn’t hold your breath.

The next part is simple, just use a modern DSLR / mirrorless camera and shoot in raw. Expose to the right, but don’t clip.

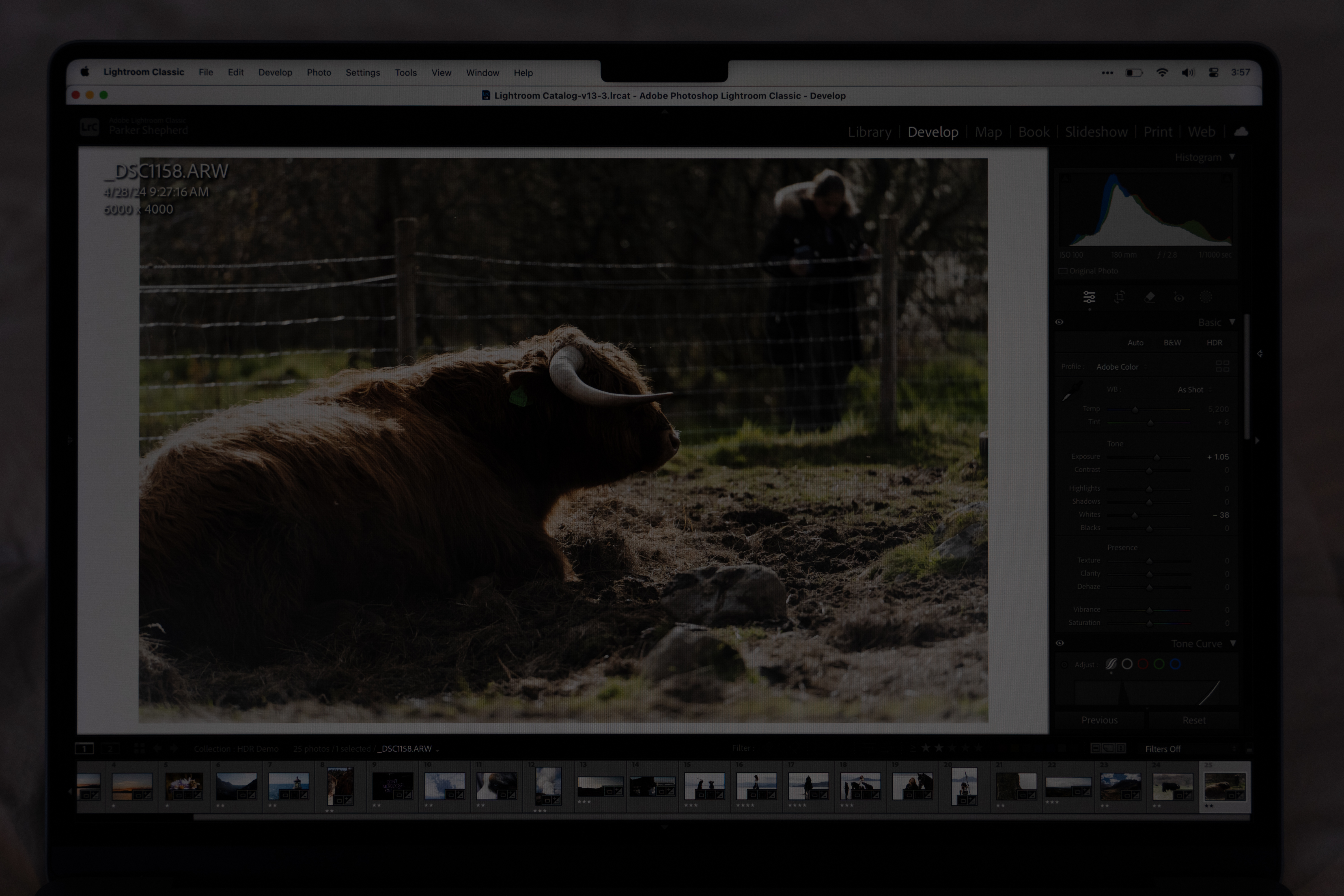

Lastly, the easiest way to get started is to use Lightroom Classic’s “HDR” button in develop mode. Affinity Photo, Pixelmator/Photomator, and a few others also support HDR but Lightroom seems the best implemented right now.

Once you’re in HDR mode, Lightroom will show you how many stops extra your monitor supports, and the histogram shows you if you’re actually taking advantage of it or not. Unfortunately, instead of getting highlight compression at that limit you’re going to see some form of clipping at the monitors limit (technically it’s up to the monitor but that’s just passing the buck if you ask me), so I’d recommend staying within your monitors limits. You can open HDR images in Photoshop (courtesy of the Camera Raw dialog) but you’re stuck in 32bit mode which means not all filters/features/plugins will work. If you convert to 16bit (or less) you’ll drop out of HDR mode. If this is a dealbreaker for you, you may still find value in photobashing in SDR, but toggling back to HDR for specific figures that need it.

Can I share my HDR pictures with others?

Kind of.

Adobe Lightroom’s “JPG with HDR output” is probably the best way to share HDR right now. Lightroom applies an algorithm to compress the photo to an SDR image (similar to the “HDR effect” you may have noticed in real estate photos, but a bit better), and then includes extra metadata in the form of a “gain map”. Your computer can combine the two images to take advantage of however much HDR headroom your screen supports, but you’ll still get a usable SDR image if not that isn’t just awkwardly clipped. If your goal is preserving detail (like in reference photography) this is a really good default, and Lightroom does have some controls for tweaking the SDR image (under “preview for SDR”) but it will affect the contrast of your SDR image so you’ll have to make your own choice if you’re delivering these JPGs as your final product to someone.

The Lightroom “JPG with gain map” images work great in Chrome, but have limited support elsewhere.

Could I make physical media HDR?

In short: no, paints don’t have enough dynamic range.

In long: maybe? To meet the traditional expectations of HDR content, you need highlights that are brighter than “diffuse paper white”, since paint/media can’t reflect more light than it receives, you would need to pretty much guarantee a bright light source is directly shining on your art, then make the piece darker than you normally would to compensate. To prevent the bright light from washing out your darks, you might have to deal with glossy finishes, insist on your work being shown in a dark room, or playing with esoteric paints like vantablack to push your darks darker (although I don’t think they play nice with blending so that might not actually help you much). The transition of thinking about your art as “art + light source” is certainly a shift, but if you’ve ever walked through a gallery displaying stunning metal prints, you’ll see why they set up shop the way they do.

Early adopters unite!

Yes, we’re in the early adoption phase, and if software support for computers doesn’t improve there’s a chance this HDR stuff will all die out. I think DolbyVision has gained enough traction that HDR is going to stick around and phone, tv, and computer support is common enough that’s it’s practical to get started now.

Early adoption is also a chicken-and-egg situation: support comes once there is demand, but demand increases when there is support. I was stunned when I toggled on HDR mode on photos I had taken years prior to learning about HDR, and selfishly I want to have more of these moments with other people’s work too. If you take any HDR photos, or better yet, discover a previous photo that works well in HDR, please share it!